By Anthony Faiola / Stefano Pitrelli contributed to this report

VATICAN CITY — Catholic saints are said to be the stuff of miracles, celestial servants who bend God’s ear to aid the desperately ill. But Pope Francis may be sending a new message to the globe’s roughly 1 billion Catholics.

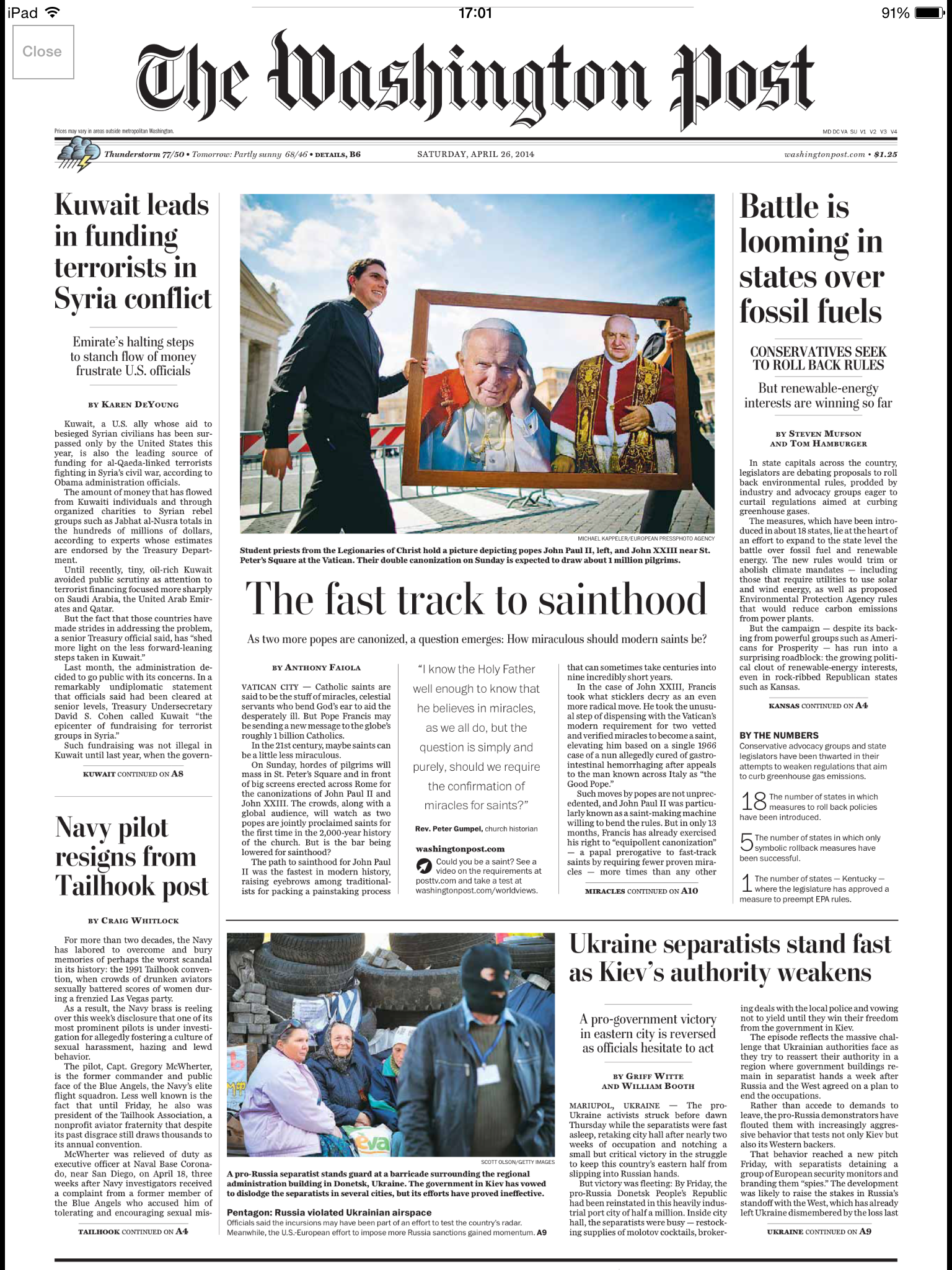

On Sunday, hordes of pilgrims will mass in St. Peter’s Square and in front of big screens erected across Rome for the canonizations of John Paul II and John XXIII. The crowds, along with a global audience, will watch as two popes are jointly proclaimed saints for the first time in the 2,000-year history of the church. But is the bar being lowered for sainthood?

The path to sainthood for John Paul II was the fastest in modern history, raising eyebrows among traditionalists for packing a painstaking process that can sometimes take centuries into nine incredibly short years.

In the case of John XXIII, Francis took what sticklers decry as an even more radical move. He took the unusual step of dispensing with the Vatican’s modern requirement for two vetted and verified miracles to become a saint, elevating him based on a single 1966 case of a nun allegedly cured of gastrointestinal hemorrhaging after appeals to the man known across Italy as “the Good Pope.”

Such moves by popes are not unprecedented, and John Paul II was particularly known as a saint-making machine willing to bend the rules. But in only 13 months, Francis has already exercised his right to “equipollent canonization” — a papal prerogative to fast-track saints by requiring fewer proven miracles — more times than any other pontiff since Leo XIII, who served from 1878 to 1903. In three cases, Francis elevated saints without a single confirmed miracle under their virtuous belts.

Francis has yet to spell out his rationale, and in the benevolent dictatorship that is Vatican City, it is not in the nature of clerics to demand explanations from a reigning pope. But for better or worse, Francis’s tendency to bypass the normal channels for certifying miracles is generating friction inside the ancient Vatican walls even as it reignites an age-old debate over the nature of Catholic saints.

Some hope that the reforming new pope is moving to modernize the image of saints. The time has come, they say, to shift the emphasis from the mystical nature of saints toward their status as role models. Still others are pressing for a new definition of miracles in the Internet age, embracing not just vanished tumors and healed aneurysms but also drug addicts who quit and divorced couples reunited after praying to prospective saints.

“I know the Holy Father well enough to know that he believes in miracles, as we all do, but the question is simply and purely, should we require the confirmation of miracles for saints?” asked the Rev. Peter Gumpel, a senior Vatican figure and church historian.

One camp in the church is all in favor of lowering the bar. Such a move could open the door to more and faster-made saints, who tend to serve as public relations dynamos for the faith in their countries of origin — a fact seen as a huge bonus as the Vatican casts its eye on fast growth in Africa and Asia. It could also pave the way to the quicker elevation of potential blockbuster saints such as Mother Teresa, whose first miracle, recognized by the Vatican in 2002, has been challenged by doctors and who is still waiting for confirmation of a second.

The proclamation of saints “helps strengthen the faith of the people,” said the Rev. Slawomir Oder, the Polish monsignor who presented John Paul II’s case for sainthood to Vatican judges.

Yet just as in other areas where the new pope is upending conventions, Francis’s actions are touching a raw nerve with traditionalists.

The belief that Catholics can directly pray to saints to intercede with God on their behalf remains a fundamental division between them and many Protestants. If more saints are created without vetted miracles, critics argue that the glow of the faith could fade for millions of Catholics who turn to saints in times of need.

“Francis has caused some apprehension among the Vatican saint-makers, who see the pope waving his hand and saying we don’t need to follow these rules as much,” said John Thavis, author of “The Vatican Diaries.” “They are saying, ‘We need to be very careful about how we do this.’ ”

Processes of canonization

The dozens of Vatican lawyers, medical experts and theologians involved in the minting of saints consider the process both art and science. In the old days, claims of incorruptible bodies and sweet fragrances emitting from graves were hailed as miraculous signs of saints. Today, the church largely relies on medical cures, seen as miracles only when they are instantaneous, lasting and clearly attributable to divine intervention.

Candidates are generally identified and forwarded to the Vatican from the diocese where they died, with postulators in Rome compiling reports to submit to a department affectionately known as the “ministry of saints” for review. Worthy candidates who meet the criteria are then sent to the pope, who officially deems them “venerable.”

But most can be named saints only after the identification and vetting of miracles. Such claims are verified through exhaustive, if secretive, reviews of documentation including witness testimony and, if available, medical tests. In most cases, one miracle qualifies a candidate for the intermediate step of beatification, while two are required for outright sainthood. Martyrs — or those who died in the name of the church — only need one miracle on their rise to sainthood.

Advanced medical technology might seem to explain away most seemingly miraculous phenomenon. But Vatican experts involved in the process insist just the opposite. They cite, for example, the before and after brain scans of Floribeth Mora Diaz — a Costa Rican woman who said she was cured of an aneurysm in 2011 after praying to John Paul II — as the kind of open-and-shut case made possible only by grace of modern science.

Describing her ordeal this week in Rome, Mora, 50, said her aneurysm abruptly disappeared after she watched John Paul II’s beatification on television and prayed for his aid. “I heard a voice saying, ‘Get up and do not be afraid,’ ” she said, her voice trembling. “I knew that I was not alone.”

Yet critics who believe in the mystical abilities of saints argue that when a pope pushes them through without the requisite number of miracles, their powers to intercede with God become more assumed than established. The Rev. Marc Lindeijer, a senior church official in Rome who compiles cases and serves as an advocate for prospective saints, compared elevating saints without vetted miracles to allowing “everyone to be a major league baseball player.”

“I believe in quality rather than quantity,” Lindeijer said. He later added, “Even if you are the president of the United States or Bill Gates, you can’t buy a miracle. Miracles are a great protection of justice, a sign of approval from God.”

Changes in the rules

Yet other observers say Francis, like many before him, is simply cherry-picking favorites, fast-tracking select candidates to save them from a Vatican bureaucracy with a backlog of thousands.

Indeed, in many ways, Francis is continuing the legacy of John Paul II, who changed the rules in 1983 to require fewer proven miracles and ended up proclaiming 482 saints — more than in the previous 600 years combined.

Francis also appears to be making a statement by canonizing a conservative pope and a liberal pope together.

While Francis did not start the process for either pope, it was up to him to decide whether to proclaim them saints now. Roughly three out of every 10 popes have become saints, the majority from the first centuries of the church’s founding. But the drive to elevate popes has accelerated in recent decades, and pressure to canonize John Paul II began at his funeral in 2005 when distraught mourners cried out “Santo subito” — or “sainthood now.”

For all his rock-star status as the first truly global pope, John Paul II also became known for his staunch opposition to birth control and divorce, as well as demands for clerics to show strict obedience to the Vatican. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, a fellow conservative and longtime confidant of John Paul II, championed his cause by dropping the traditional five-year waiting period to begin the process of sainthood.

Though opponents have charged John Paul II with turning a blind eye to widespread reports of sexual abuse within the church, the pressure to canonize him was so great that insiders say it would have been next to impossible for Francis to avoid it.

Yet Francis appears to be balancing the statement made by rapidly anointing John Paul II by also fast-tracking John XXIII. A jolly, roly-poly pontiff known across Italy as “the Good Pope,” John XXIII set in motion the Vatican II Council, credited by liberals with softening church doctrine and moving away from Masses once said only in lofty Latin. In fact, in Francis, many observers see a leader very much like John XXIII.

“Look, if you can’t break a few rules, what’s the point of being pope?” said the Rev. Thomas Reese, author of “Inside the Vatican: The Politics and Organization of the Catholic Church.”

Stefano Pitrelli contributed to this report.