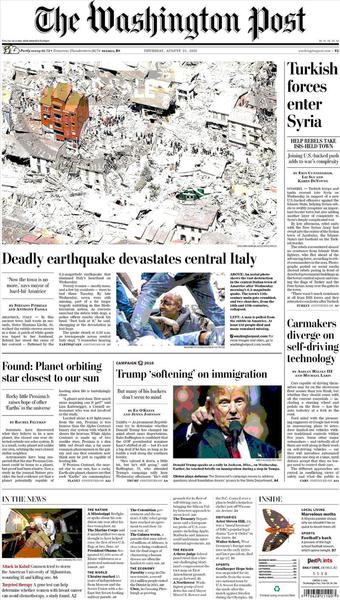

Rescue workers struggled to reach survivors amid the rubble. Thousands were left homeless.

by Stefano Pitrelli and Anthony Faiola, The Washington Post

her convent — flattened by the 6.2-magnitude earthquake that slammed Italy’s heartland on Wednesday.Twenty women — mostly nuns, and a few lay residents — went to bed there Tuesday. By late Wednesday, seven were still missing, part of a far larger tragedy unfolding in this Mediterranean nation. As rescuers searched the debris with dogs, a police officer nearby shook his head. “Just look at it,” he said, shrugging at the devastation in lost hope.The quake struck at 3:36 a.m. as townspeople across central Italy slept. “I remember hearing something, a loud noise, and then hiding under my bed,” Lleshi said. “I was screaming, and I got out and started running when the ceiling started coming down.”A young man who was staying overnight at the convent found her in the chaos and guided her to safety. “All I could see was destruction around me,” she said. “I had lost all hope to get out of this alive, but God sent me his messenger.”On Wednesday, many others across a vast swath of quake-prone Italy were not as fortunate. Early Thursday, Italian authorities said at least 247 people died in the quake, a toll that could jump as search crews rake through the rubble in cities, towns and villages across the regions of Lazio, Umbria and the Marches. Hundreds were injured and missing. Thousands were left homeless.

A powerful 6.2-magnitude earthquake ripped through towns in central Italy in the middle of the night on Aug. 24, leaving fatalities and rubble in its wake. (Video: Jenny Starrs/Photo: REMO CASILLI/The Washington Post)

Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, speaking from northern Lazio, looked beyond the rescue operation to the huge task of rebuilding. “The credibility and honor of us all will be in granting a true reconstruction that allows the residents to live and restart,” he said.

This part of Italy — known for its gently sloping vineyards and olive groves, and its precious towns of cobblestone streets — was already confronting a plague of economic stagnation, its population aging and decreasing. Not as rich as Italy’s north or as aid-worthy as its poorer south, it is a part of the country where investment in infrastructure lags.

Yet the vacation month of August is when the area’s towns come alive with part-time residents and tourists — a fact that officials said could drive the death toll up.

Buildings swayed from Rome to Venice. But large parts of Amatrice — a town of 2,700 known for supplying the chefs of popes and the recipe for one of Italy’s greatest pasta dishes — were left in total ruin. Amatrice was among the worst hit, part of a list of unlucky towns including Accumoli, Posta and Arquata del Tronto.

This weekend, Amatrice was to host the 50th annual Spaghetti Amatriciana Festival — a celebration of its famous tomato-and-pork-jowl pasta dish that was scheduled for the town square. That square is now a pile of rubble, and Amatrice is counting its dead.

The 15th-century main gate to the town — which resisted invasions and past earthquakes — crumbled.

“We were used to earthquakes, but now the town is no more,” said Amatrice Mayor Sergio Pirozzi. “We will keep on digging. Hope is the last to go.”

In town, people draped in white blankets stood shell-shocked next to destroyed buildings. Before-and-after aerial pictures showed the magnitude of the destruction.

On the town’s dusty, devastated streets Wednesday, the bell-tower clock was stuck at 3:36. Three women walked on restlessly, one of them in a panicked search for a family friend. All around, rescuers plucked away at rubble with heavy machinery, pickaxes and bare hands.

At one point, 10 men with a search dog pinpointed a possible survivor — or body — buried in the rubble. They labored feverishly in the debris of a ruined building.

There were moments of relief and joy — several survivors, including a small girl, were pulled alive from debris. But random scenes of tragedy also unfolded. One rescue worker ran across a street, for instance, telling another in resignation about the fate of a possible survivor. He simply said, “Marco, he’s dead.”

And there were heroics. “My brother, he risked his life to try to save his wife,” said a distraught visitor, Nunzia Onori, 59. “He ran back into the house to save her while it was collapsing. He tried so hard. But she did not make it. It makes you want to cry.”

Yet many here mourned for the town itself — for so much history lost.

“It’s horrific, horrific. Everything has been stolen from us — from an economic perspective, a social perspective and a cultural perspective,” said Luca Faccenda, 65.

The main earthquake, a shallow six miles below ground, was centered about 106 miles northeast of Rome. A string of aftershocks as strong as magnitude 5.5 continued to hit the affected zone, and the damage was far-flung, with some of the worst devastation in Lazio.

In Accumoli, another hard-hit town in Lazio, Mayor Stefano Petrucci described extensive damage and casualties.

“Four people are under the rubble, but they are not showing any sign of life, two parents and two children,” the mayor told the RAI news outlet.

Authorities called on residents in affected provinces to avoid congesting roadways to help rescue workers. Appeals were issued for blood as hospitals dealt with a rush of earthquake victims. The Vatican dispatched its fire brigade.

Speaking in St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City, Pope Francis said: “I cannot but express my great pain and say I am with the people in all the places stricken by this earthquake.”

The quake evoked memories of 2009, when a 6.3-magnitude quake struck farther south, killing more than 300 people. That quake was centered around L’Aquila, about 54 miles south of the latest quake.

Rémy Bossu, head of the European-Mediterranean Seismological Center in France, said shallow earthquakes of this magnitude are not highly unusual in the zone hit Wednesday. In addition to the L’Aquila earthquake, another hit Umbria and the Marches in 1997 that severely damaged the famous Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi.

He said the main problem in the area was the large number of older buildings that cannot withstand earthquakes of this magnitude.

“The problem is that the [earthquake-proof] building code only applies to new buildings,” Bossu said. “To retrofit an old building is a very complex and costly operation. So it’s only done for key buildings, such as hospitals.”

In Amatrice, many of the buildings were not reinforced to withstand earthquakes of this size — including the 1940s convent with the missing residents.

Even as the search continued at the convent late into the night, there were no immediate signs of hope. Church officials said many women had still not been found.

Humans “are fragile, vulnerable to danger,” said Domenico Pompili, the local bishop. “This is a time of challenge, a time for rescue and a time for prayer.”

Faiola reported from London. Stephanie Kirchner in Berlin and James McAuley in Paris contributed to this report.